Narrowband for Stars

nb4stars

Introduction

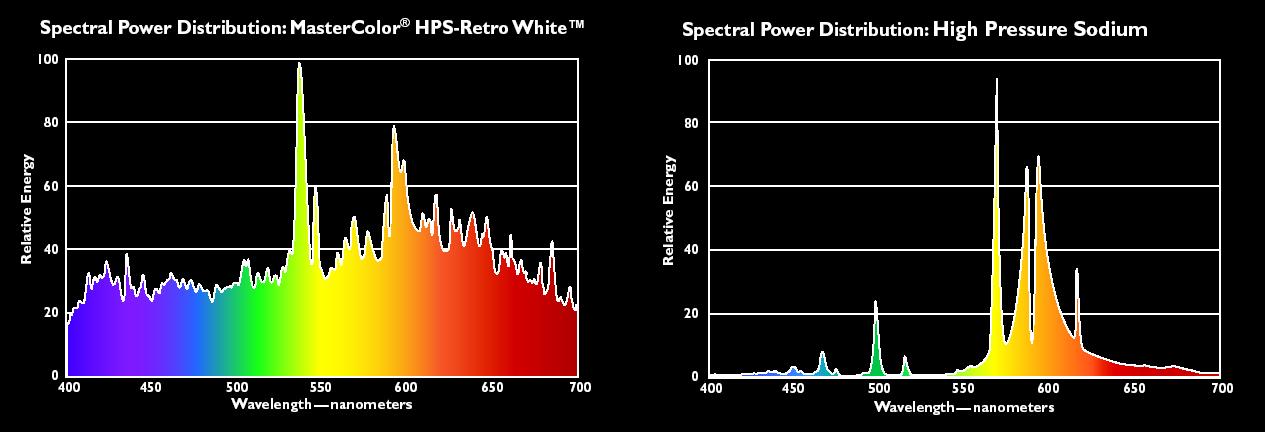

Sites located close to urban centers are cursed with light pollution. More and more of the visual spectrum is disappearing as cities and companies move from the relatively astronomy friendly Low Pressure Sodium lights to more broadband types of lighting such as LED, HPS, and Metal Halide. Ultra Narrowband imaging works well for nebula since high quality 3 nm filters eliminate most of the city light (and much of the moon light). Unfortunately, galaxies and star clusters are made from stars that mostly shine in the same visible light bands as are being lost to the scattered city lights.

My assumption when I first began imaging in late 2010 was that light pollution would not allow me to do conventional LRGB from my location.

I was convinced at AIC 2011 to try LRGB. I bought a set of LRGB filters and gave conventional color a shot using M33 to the left. The results did prove that I could take LRGB pictures; however, M33 transits almost directly overhead.

Visit the 2011 - M33 Project

Spring time objects are located in a more polluted part of the sky. The more subtle portions of the galaxies are lost in the city glare. The reason is obvious. LRGB depends on taking a very deep and high quality L image. This image is then colored using lower quality R, G, and B data (enhanced by H data also).

The problem is that at my site even a 7 minute L exposure contains a significant light gradient. The image on the left shows the amount of gradient I have to deal with. While this can partially be removed, this adds noise and also erodes the dimmer details. This image was taken on a night with transparency we only see a few times a year. Thus on most nights the gradient would be much worse. You can see this in my LRGBH project of M101.

By June 2012 it was clear that my original assumption was correct. I realized that I was not going to be satisfied with LRGB images taken at my site. That is when I started looking at alternatives.

Rather than fight (or accept) the light pollution I decided to try a different approach. An astronomer at Kitt Peak suggested I look at Photometric filters. These are more narrow than regular LRGB (especially the L which is effectively the entire visible band). This approach is similar to the "Skylight" and "UHC" filters I use for visual work. The idea is to admit enough light to be useful, while excluding light pollution. This is a tricky balance that I will explain more below.

Examples of Narrowband 4 Stars (Ha20, sYel, sV)

Before I go into the technical details of what I am trying let me first present some projects that used my latest approach.

Theory Behind Narrowband for Stars

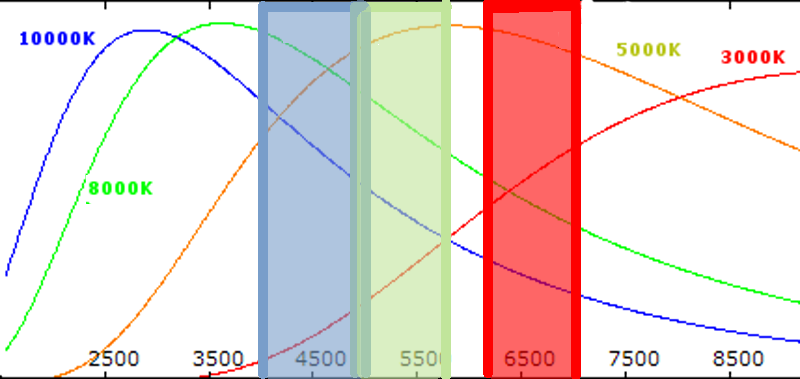

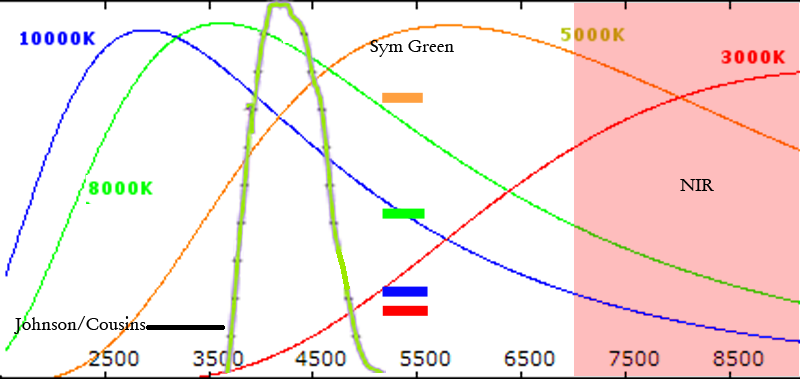

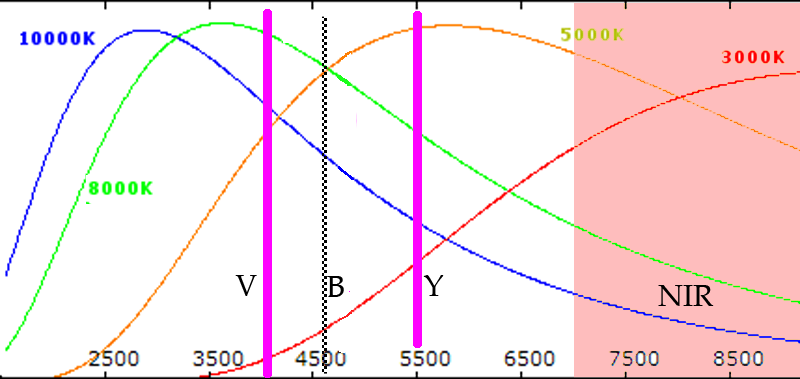

When you are photographing galaxies and star clusters you are fundamentally taking pictures of stars (OK there is Hydrogen present and maybe other nebulosity, but that can be added separately as I did above). Stars emit based on black box curves called Plank Curves. The curves for 4 different types of stars are shown below. For more information see the Appendix. Each of the RGB filters sample a portion of the Plank curve. When combined they reproduce an Astronomical Color Image1. Note the small overlap. At any particular wavelength only a single color filter is registering (with the exception of the small B/G overlap). When the signals from each of the filters is combined it reproduces a representation of the perceived color of that combination of wavelengths

My technique is different from normal LRGB in two ways.

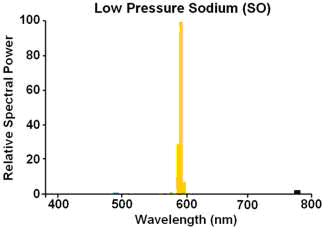

- I am not using a Luminance image. A Luminance image is subject to light pollution over the entire visible spectrum including the gap between G and R which includes LP Sodium.

- Instead of an FWHM for each color of about 100 nm I am only

gathering 16-20nm (depending on the filter). This narrower band

tries to exclude more of

the light pollution bands while sampling enough of the Plank curves to

give a meaningful representation of star color.

If I was imaging rainbows this would never work, but since I am imaging a Plank curve it will. The trade off is longer exposures due to the smaller FWHM.

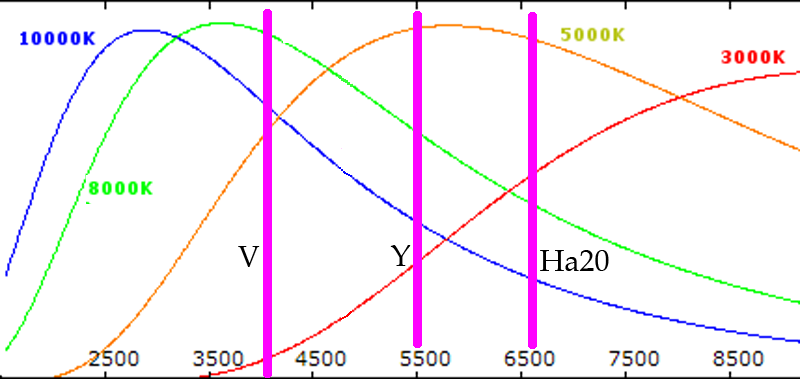

Strömgren/Ha20 (sV-sYel-Ha20)

The Strömgren system is a method of measuring the metallicity of stars. For this technique I use 3 filters which I designate sV (410nm, FWHM @ 16nm), sYel (550 nm, FWHM @ 19 nm), and an 20 nm Ha{+N II} filter. Each of these samples the curve as shown above. The three are initially combined using a simple ChannelCombination subject to later Color Calibration as described below. Using an Ha filter for red has a couple of advantages over using an NIR filter as I did before. The first is that it captures Hydrogen alpha data directly with enough filtering that it should be directly usable. The second is that it will directly sample the red intensities of stars.

Another advantage of this combination is that I can use it to image star clusters that are also Sharpless Objects. The Ha20 will capture the Hydrogen directly; However, adding additional 3nm Ha and OIII (which my system does not collect) will let me reproduce the colors more accurately.

I have to credit Don Goldman for suggesting the 20 nm Ha {+N II} filter. He originally built for a university project. When I described what I was trying to him he suggested using that instead of the NIR filter I was previously using.

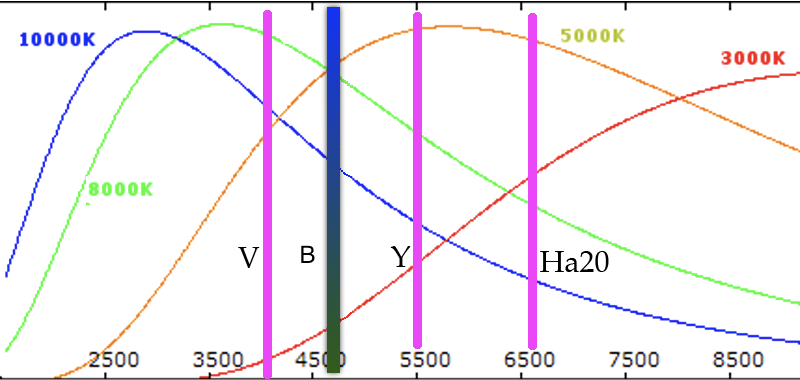

Strömgren/Ha20(sB-sYel-Ha20)

Starting in 2017 I switched to using the Strömgren B filter (467 nm width 18 nm) instead of the sV. My camera is more sensitive to this band which will result in sB being closer in intensity to the other two filters. The one remaining question is whether this filter is subject to pollution from from the approaching LED lights. At the moment these are not close.

Color Calibration

The camera's sensitivity will vary with the filters being used. Also the atmosphere will refract the violet stronger at lower elevations. Thus the raw images require color calibration. In practice I have used two methods

- G2V (see also). I use broader catalog than either of these sources to select a star. I then take an image with each filter. The ratio is determined by measuring the total strength using Maxim. I then plug that ratio into PixInsight's Color Calibration tool. This sounds all nice and clinical, but the G2V ratio depends on the star's alt az. Since I can image for several hours the alt az will vary with exposure making this somewhat less accurate for objects that do not transit overhead.

- PixInsight White Balance The alternative is to use PixInsight's Color Tool to select a part of a galaxy as a white reference and then adjust the ratios itself

Look at the individual projects to see what I have chosen

Older Approaches

The following discuss the previous filter techniques I have used.

Johnson/Cousins (NIR-SynG-pB)

The first technique I tried is to sample the Plank Curves using the B filter of a Johnson/Cousins UVBRI filter representing the Blue channel. Near Infrared Luminance filter (>700 nm) supplies the red channel. The Green Channel is created using the min(pB, NIR). As I looked at the result I understood the science that was making this work.

Since the green channel was a SWAG this approach was intellectually unsatisfying. Also the B filter was also subject to light pollution and was likely to be more greatly affected in the future. Since the entire reason I was doing this was to avoid light pollution this approach was abandoned in favor of the Strömgren filters.

Strömgren_sV-sYel-NIR

In Winter of 2013 I ran some tests with this filter system. These were all taken with an 8300-based camera. The principle disadvantage of this approach is that dim M type stars are suddenly some of the brightest in the image. That erodes the "just like color" goal.

Conclusion

Short of moving to central Nevada light pollution is something I have to deal with. There are ample sources of light to corrupt a luminance image. By going to narrow and using selected bands as a proxy for a full width filter I can avoid as much pollution as possible while still collecting meaningful data.

Where to get the Filters

Strömgren filters used to be available via Astrodon. Unfortunately they discontinued them a couple of years ago. As discussed below Johnson/Bessel (UBVRI) won't work because they are two broadband. The Ha20 filter was always a special order.

A web search turned up that Custom Scientific may sell Strömgren filters on special order. I also found Ha20 filters from Farpoint.

Appendix

More About Star Colors

| Star Type | Temperature | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| B | 10,000 | Rigel, Spica |

| A | 8,000 | Summer Triangle. Sirius |

| F | 6,000 | Procyon |

| G | 5,000 | Sun like stars |

| K | 3,500 | Arcturus |

| M | 3,000 | Betelgeuse, Antares, and red dwarfs |

Affects of Light Pollution on the filters

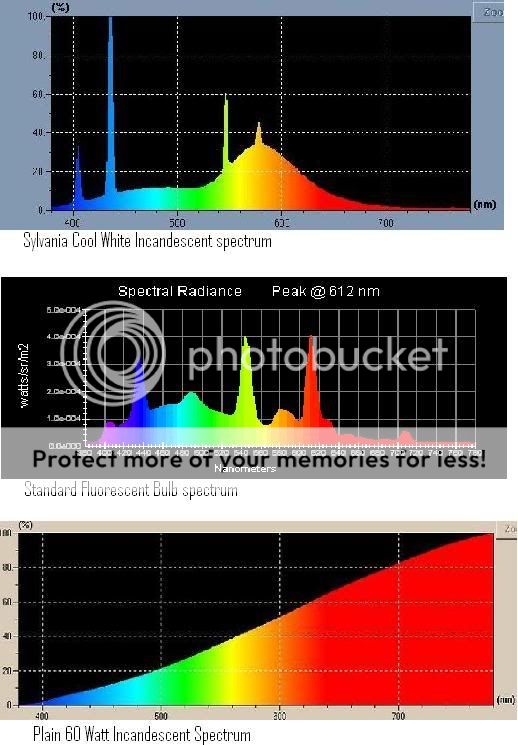

Since avoiding light pollution is the central theme of this entire effort it is useful to understand what I am avoiding.

Scattering of Light

Light pollution makes its way to my telescope because it is

scattered (I am excluding the light trespass from one of my neighbors).

There are several types of scattering which are described in detail

here.

For the purposes of this discussion

Rayleigh

scattering is biggest problem. That affects blue

more than green more than red. Thus a similar intensity in blue is more

of a concern than an equivalent one in red.

Low Pressure Sodium

These remain the most astronomy friendly of the choice;

however the L in LRGB will see the reflections of this light.

LED Streetlights

San Jose like many cities is replacing its LP Sodium street lights with LEDs. The LEDs use less electricity and (at least in theory) be dimmed or shut off by timers or motion sensors. The big BUT for astronomy is the spectra of the most common LEDs. IDA is trying to convince San Jose to use LEDs that do not contain the Blue spike.

The sV filter would avoid most of the bright 450 nm emission from this type

of LED while still sampling the A and hotter stars.

Unfortunately the sYel filter will be right at the 2nd peak of the LED

as well as near the brightest emission of many of other light pollution

sources. The sYel filter does avoid the strongest peaks of some HPS.

I initially rejected using the Strömgren B (470 nm) filter due the the strong emission of this type of LED streetlight. Since I started using the Optec EL Panel I have had to also start using the B and just accept any light degradation.

High Pressure Sodium and Mercury

A tennis court and country club located near my house uses one or both of these type of lights. Fortunately they are good neighbors and have generally shielded their lights.

Incandescent, Halogen, and Mercury

Vanity and insecurity lighting from my neighbors is one these. I have Halogen security lights also and they are very bright, but they are only on when I need them to be.

My sky is also saturated with the glow of low pressure Sodium courtesy of street lighting.

Notes

1 I use the term "Astronomical Color Image" since the filters used in LRGB astronomy work differently than those used in one shot cameras. Using astronomical filters any single wavelength except about 500nm is either R, G, or B. There are no yellows or violets except when a pixel is illuminated by different wavelengths. If a pixel is illuminated by 656, 486, 434, and 410 nm in the right proportions the resulting color will be the pink of Hydrogen.

Humans see rainbows because their vision works very differently from that of an astronomical CCD. CCDs used in everyday cameras also work differently. They contain a different filtering scheme that uses using relatively broad filters which work similar to how human eyesight works. Thus rainbows look like rainbows because the overlapping filters are able to produce a wider range of colors than non-overlapping filters can.

For this work I am only trying to equal the performance of Astronomical camera. A technique that samples the entire Plank Curve will reproduce it differently.